Adrian Tennant looks at how most exams test a student’s ability to do tests and gives some practical tips aimed at helping you prepare your students.

Introduction

Although most English language tests claim to assess the proficiency or ability of a student, the reality is quite different. Almost every devised and administered test assesses a student’s ability to do that particular test, and not their overall competency in English! Tests have a particular format and set of tasks. Familiarity with the format and the task type almost always results in a higher score. Therefore, the test in question does not only test a student’s language ability, it also tests their ability to do the test.

Why have tests and exams?

Tests and exams are here to stay. There is no point spending too much time criticising their very existence, as there are far too many people with an interest in them. Schools want to know how well students are doing; parents want to know how well their son or daughter is doing; often students themselves want to have some form of measurement; employers or potential employers want to know how good someone’s language skills are, etc. So rather than fight against them we need to look at ways we can address their inadequacies and help our students tackle the inevitable.

Preparing students

There are a number of key steps in helping our students when they are faced with tests.

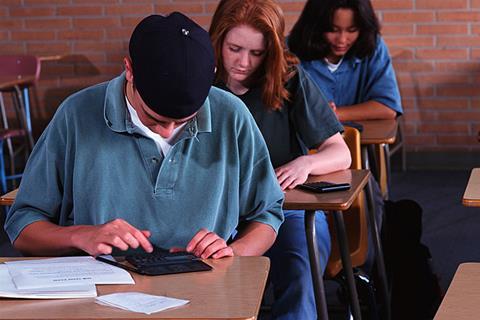

Firstly, we have to try and make the whole process as unthreatening as possible. Of course, it is common for students to feel stressed before they take a test. However, an element of stress can sometimes be a good thing. One way to make tests relatively stress free is to make them a common occurrence within the classroom and learning environment. Giving regular tests and assessments to students and using the results as a learning tool means that students feel less worried about taking them.

Secondly, students need to be familiar with the format. As pointed out in the introduction, knowing the format almost always leads to a better score. This does not necessarily mean taking lots of tests and practising them to death. It means knowing what each paper looks like, how many questions there are and what each question is actually trying to assess.

This leads me onto my third point. If students are aware of what each part is trying to test, they will be better equipped to deal with the question or task. This does not mean that they need to do lots of questions in class or for homework, it means that each question or task type needs to be picked apart and analysed.

A multiple choice example

Let’s have a look at an example. Multiple choice questions are a common task type in tests. What they test depends on whether they are part of a grammar, vocabulary or skills comprehension task. However, what they all have in common is the way they are presented.

Here is an example:

a) few b) many c) much d) often

In terms of presentation, I am not referring to the gap and the four choices. I’m highlighting the fact that the choices are there to distract the student and, in a way, confuse them a bit. One technique we can teach our students is to cover up the four options, look at the sentence, try and decide what word will go in the gap and then look at the choices to see if there is one that matches their original thought. We can also point out that there are clues to which answer is correct. For instance, the above example is a question, so we can immediately dismiss the word which is not used in a question. Also, the focus is on the word know not tests. Know is uncountable so we can discount many, which is put there to confuse us. Teaching students to eliminate ‘wrong’ answers helps them narrow down the choices and gives them a better chance of choosing the correct one.

These techniques aren’t developed simply by practising and practising but rather by focussing on the process, discussing it and then practising it enough to make it part of the student’s repertoire. In other words, training our students to take (and pass) the test.

The ‘washback effect / backwash effect’

This refers to the effect that the test has on classroom teaching. In many cases, classroom teaching is geared towards getting our students ‘through’ the test. It is questionable whether this is a positive thing – surely there is more to learning languages than simply passing tests?

One of the problems is that tests are often designed to be easy to administer and mark. Multiple choice tests are a good example of this. They are relatively easy to design (although there are lots of examples of poor multiple choice tests where more than one choice is correct, or none!) and very easy to mark – in fact, they are often marked by computer. However, they do not reflect what usually goes on in a language classroom in terms of our teaching. We therefore have to teach for the test, creating a backwash effect.

Some (more) practical ideas

Build up confidence

I’ve often seen students give up as they find the task too difficult. In fact, they may well have the language ability but they simply don’t understand what they are supposed to do. For example, when students first see an Open Cloze (a text with gaps with no choices given) they don’t realise that there are a limited number of words to consider.

One way to prepare students for this is to start off slowly. Give students an Open Cloze text and ask them to work alone, then put the students in pairs and get them to compare their answers. Meanwhile, write up the answers plus three extra words on the board in a random order, i.e. at, have, has, in, etc. Next, tell the students to look at the board and compare the choices with their answers. Point out that there are some extra words. Finally, while checking the answers together, discuss the type of words which were left out and the clues that were in the text to help the students ‘guess’ the correct word.

Turn it into a quiz or game

Exam classes do not need to be boring. Simply practising test tasks and questions is not only a fairly useless way of preparing students for tests, but it is also a guaranteed way of putting them off learning. However, making them part of the lesson and into fun activities can be quite easy. For example, turn a multiple choice task into a quiz:

- Divide the class into teams.

- Give each team a sheet with the choices.

- Display the text on the board.

- Tell the teams they have ten minutes to discuss the answers.

- Now give each team 150 points. Tell them they can place ‘bets’ against their answers using these points (e.g. 10 points on answer 1, 25 on answer 2, etc) until they have used up all their points. If they have chosen the correct answer they will get their points back plus the same again, i.e. if they placed 10 points and they get the answer right they get 20 points. If they get the answer wrong they lose the points they placed on that answer.

- At the end, the team with the most points wins.

Analyse the purpose of the test task

In the previous task students had to decide whether they were confident with their answer. The more confident they were, the more points they were likely to ‘bet’. In some respects they were beginning to analyse the task, but it can be taken much further.

Understanding the purpose of a task helps when thinking about how to answer it. For example, knowing that an Open Cloze focuses mostly on grammar words, or occasionally on collocations, helps give students a clue as to the possible options / answers. Knowing that the four choices in a multiple choice task are there as distracters helps students cope with them and not get so easily misled. Therefore, it is worth looking at test tasks and asking a number of key questions:

1. What is the task testing?

2. How is it testing it?

3. How am I supposed to know the answer?

4. What is the best technique to use to get the correct answer?

5. Are there any things to try and avoid?

Look closely at the rubric / task instructions

One thing that students often fail to do is read the instructions carefully. For example, in a Cloze test the rubric often states: Complete each gap with ONE word only. Yet students often put two or three words in the gap. There is a tendency to make assumptions, so if a task looks familiar students go straight ahead and answer the questions without first reading the instructions.

Training your students to always read the instructions is an important thing to do. One way you can teach this is by playing a simple game. Hand out a worksheet like the one below, and wait to see what happens.

INSTRUCTIONS WORKSHEET

1. Read all the instructions before you start.

2. Write your initials in the top left hand corner.

3. Write the date in the bottom right hand corner.

4. Write your favourite colour in the left margin.

5. Do the following sum: 7 x 9 + 30 ÷ 3 = ?

6. Write the answer at the top of the page.

7. Write the answers to these questions only if your first name and surname begin with the same letter.

Almost every time students will follow the instructions one at a time and won’t read them all through first – despite the fact that the first instruction tells them to do precisely that. Try this and then discuss the importance of carefully reading all the instructions before launching into the task.

Get your students to design their own test tasks

My final tip is to get your students to design their own test tasks. By doing this students get a better understanding of what a task is actually testing and therefore a better idea of how to best tackle a task.

It’s easy to organise. For example, if you want your students to practise a multiple choice Cloze task, give them a text (this can be a short reading passage from their course book) and ask them to choose 10 words to test. Give the students whitener to blank out the words they want to test. Then get them to write the multiple choice options for each gap, including the one correct word. Once they have finished they can give the text to another student (or pair of students) to try and complete. If students are using the same text, give them out in the following lesson so that they are less likely to remember the exact wording of a text.

Good luck! And happy testing!

Assessment matters: Designing your own tests

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

Currently reading

Currently readingAssessment matters: Preparing students for tests and exams

- 9

- 10

- 11

No comments yet