Carol Read offers practical guidance on content-based learning, including tips for choosing suitable cross-curricular topics and activities.

The inclusion of content from other areas of the curriculum has long been a feature of some primary foreign language programmes. In recent years, content has been given greater prominence as many countries or regions have lowered the compulsory age of starting to learn a foreign language at school and increased the number of study hours through the introduction of programmes based on Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL). CLIL is an umbrella term which encompasses many different approaches in which part or all of school subjects are taught through an additional language. As a common feature of CLIL, there are aims, procedures and outcomes which relate both to the subject being taught and to the language. The focus of this article is on including content from other areas of the curriculum in English language learning programmes, rather than on teaching specific subject syllabuses through English. As well as making lessons more intrinsically interesting, the inclusion of content can enhance and extend children's learning and acquisition of language. It can also contribute to their social, cognitive and psychological development.

Throughout their primary education, children are developing their knowledge and understanding of the world. At the same time, they are developing their ability to use language as a tool to investigate, analyse and describe the world. This inter-relationship underpins and links different subject areas across the primary curriculum. On the one hand, language is the medium for learning about all other subjects and, on the other hand, all other subjects are the vehicle for developing language.

When children start learning a foreign language as a school subject, this is often isolated from the mutually reinforcing process of developing knowledge and developing language that enriches all other areas of the curriculum. The reason for this is not surprising perhaps, as, initially at least, it seems difficult to envisage how English may be used as the medium to learn about other subjects when children's language competence is so limited. By adopting an approach which integrates content-based learning from the earliest stages and most elementary levels, learning to use a foreign language becomes part of the holistic developmental and educational process which takes place in all other areas of children's experience and learning at primary school.

How to integrate content into primary language learning

Within English language programmes there are three commonly used approaches to the integration of content. These are:

- through the organization of the syllabus and learning based on topics from other areas of the curriculum

- through the organization of the syllabus and learning based on stories

- through the use of content-based activities from other areas of the curriculum that relate or fit into an existing language-based syllabus.

Topics chosen from other areas of the curriculum should motivate and interest children and provide a suitably challenging context in which learning can take place. They should relate to and build on children's experience and knowledge of the world and provide opportunities to develop concepts, language and thinking skills in ways that are appropriate to the children's age and level. Topics should also lend themselves to the design of purposeful activities, including opportunities for investigative, factual enquiry and for creative, imaginative work. By organizing learning around topics, children's language development can be integrated with content from other areas of the curriculum in a natural way. Topics provide opportunities for meaningful, experiential learning that appeals to different intelligences and learning styles. Topics also encourage children to be active and constructive in their own learning as they use language as a tool to do things which are relevant, purposeful and enjoyable and which build on their natural curiosity in finding out about the world.

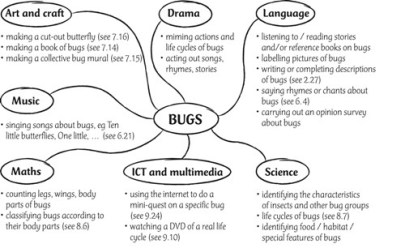

Figure 1 Topic web on bugs

Below is an example of a topic web showing how language and content from other areas of the curriculum might be integrated in a topic on bugs.

|

A similar kind of web integrating content from other areas of the curriculum may also be used if the children's learning is organized around stories.

When organizing learning which integrates content from other areas of the curriculum based on a topic or story, the use of a web, such as the above, is a flexible initial planning tool. In order to develop a coherent learning sequence, the activities need to be planned in detail and ordered in a logical way. This involves linking them so that each activity consolidates and builds on what has come before and also prepares for what is to follow. Although the activities in the sequence use concepts and skills which draw on different areas of the curriculum, the children experience a seamless series of classroom events. The activities lead children progressively to new learning in a way which is both challenging and achievable. In order to make suitable links between activities you need to analyse and plan each one in terms of:

- concepts: what concepts the activity will develop and whether these are already familiar to the children in L1

- cognitive demands and thinking skills: whether the cognitive demands are appropriate to the age and level of the children and what these involve, for example, the ability to predict, estimate, classify, describe a process, or interpret and use a graphic organizer

- language demands and skills: whether these match the cognitive demands as well as the main sentence patterns, grammar, vocabulary and language functions children will need to use; how much language will be new or recycled, whether it will be receptive or productive, and the language skills, or aspects of these skills, the activity will develop

- other learning skills and strategies: apart from language and thinking skills, what other skills, eg social skills, motor skills, learning strategies or metacognitive skills (see Section 10 Learning to learn) does the activity assume or will it help develop?

- attitudes: what positive attitudes will the activity help to foster, eg towards the topic itself or in terms of citizenship or individual learning?

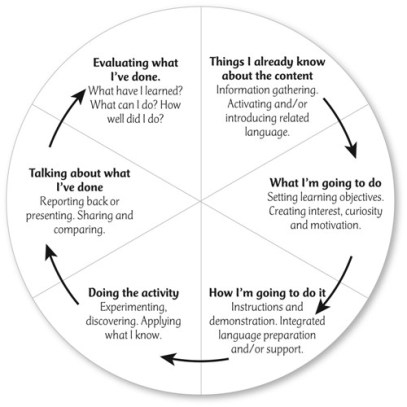

Figure 2 Investigative learning cycle

|

When implementing content-based learning activities as part of topic or story-based work, it is frequently appropriate to follow stages of an investigative learning cycle as outlined above. These broadly reflect the familiar stages of before, during and after activities but place an emphasis on ensuring the integration of content and language support needed to carry out the activity.

Many children's course books are based on either topics or stories or a combination of both. In a partial version of the approach suggested in the cycle above, content-based learning sequences can be used to supplement or extend topics and/or stories that already exist within the course book. In a full version of the approach, the detailed planning resulting from initial curriculum-linked webs based on topics or stories can constitute the entire syllabus and learning programme. While the latter has the advantage of being able to tailor learning very specifically to the children's context, interest and needs, the amount of planning time, effort and additional resources required should not be underestimated.

In situations where children are following a language syllabus which is not based on either topics or stories, content-based activities can also be included to enrich and extend learning, particularly where there is a direct link between the language of the activity and the language in the syllabus. Although this represents a much more piecemeal approach to the use of content-based learning, it does nevertheless give children an opportunity to practise language in a meaningful context and may contribute positively to their motivation too.

Benefits of content-based learning

In terms of cognitive strategies and skills, the activities develop children's abilities to, for example, estimate, hypothesize, experiment, report, classify, compare, contrast, measure, match, sequence and describe processes, as well as to use different kinds of graphic organizers and charts.

In terms of the CLIL umbrella referred to earlier, integrating content-based learning activities into language lessons where the syllabus, materials and forms of assessment are predominantly language-led, is very much the tip of the 'content' iceberg. There are, however, a number of significant potential benefits which make it extremely worthwhile, even if only on a limited or occasional basis.

- Lessons can be made more interesting, varied and enjoyable.

- Children generally find it extremely motivating to investigate, discover and learn things about the world through English.

- Language is used purposefully and the focus on real meaning is more likely to make it memorable.

- Children use different combinations of intelligences and learning styles which widens the appeal of classroom activities and allows children to build on their strengths.

- It reinforces learning and conceptual development in other areas of the curriculum, thereby bringing English into the mutually reinforcing process of developing knowledge and developing language at primary school described earlier.

- It encourages children to work more independently and helps them learn how to learn.

- It provides an approach to learning which takes account of children's whole development in a harmoniously integrated way.

- Additional benefits for individual children also frequently include increased confidence, higher levels of concentration and more positive attitudes towards learning a foreign language at school.

As you use the content-based activities which accompany this article or the worksheets available in the young learners section with your classes, you may like to think about the following questions and use your responses to evaluate how things went and plan possible improvements for next time.

- Curriculum links: How did the activity or activities relate to other areas of the curriculum? What was the main value of making such links?

- Cognitive / language demands: Were the cognitive and language demands appropriate to the age/level of the children? Was there a balance or mismatch in the cognitive / language demands? If there was a mismatch, how could you redress this next time?

- Interest: What was the level of interest in the activity or activities? How did the inclusion of content based on another area of the curriculum influence the children's response?

- Learning sequence: What was the rationale for sequencing the activities? Did the sequence allow for a smooth learning progression or would you make any changes next time? If so, what?

- Aims and outcomes: Did the activity or activities fulfill both content learning aims and language learning aims? How were these reflected in the outcomes?

- Classroom communication: How did the use of content-based learning activities influence the way you and the children communicated in class? Did this seem to enhance children's language acquisition and learning? If so, in what way(s)?

Content-based classroom activities accompany this article.

This article was taken from 500 Activities for the Primary Classroom by Carol Read (Macmillan 2007). 500 Activities for the Primary Classroom is lively and varied of ideas and classroom activities for children between the ages of 3-12.

Carol Read is an educational consultant, trainer and writer based in Madrid. She has many years' experience of teaching children and training primary language teachers in different countries. Carol is co-author of several course books, including Bugs and has also written numerous articles about teaching children. Her current interests include scaffolding children's language learning, applying multiple intelligence theory to primary language classrooms and developing primary language teacher education appropriately in different contexts.

Carol is the author of the Primary course Footprints. Written for pupils who are working at a high level of English, Footprints provides a strong emphasis on cross-curricular content with clearly identified language aims that acknowledge the increasing trend to content-based learning.

Topics

CLIL articles

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13Currently reading

Article: Content-based learning in the Primary classroom

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

No comments yet