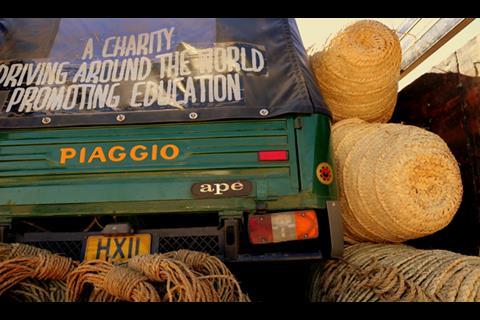

In their second travelogue, our tuk tuk boys cross the border into Sudan, experience some first-class hospitality and visit a worthy project.

Of all the countries we’re going to be passing through this year, one has always stood apart from the rest. Upon hearing our route is taking us through Sudan, most people seem to wince, gasp or go straight ahead and start saying their last goodbyes to us right then and there. Stereotypes of the dangers of Sudan and its people couldn’t be further from the truth, though.

Having arrived in Wadi Halfa by boat from Egypt, the customs process took a little longer than expected. With night falling quickly we had our first experience of Sudanese hospitality – our fixer, who had been helping us and some other overlanders enter the country, insisted that we all stay at his house. The next day, stopping in a small town in the Nubian desert to find some bread, we were invited into the bread-sellers home and spoilt with sweet tea, homemade biscuits and caramelized dates. Throughout the country we were met with broad grins and exaggerated waving wherever we went. The police, in particular, seemed especially keen to stop us at every opportunity just to say hello and try to help point us in the right direction.

The Sudanese are, hands down, the friendliest people either of us have ever met. In Khartoum, however, we were still able to witness the impact of the violence of the country’s recent past. In the 50-year war fought between North and South, many from regions of South Sudan, the Nuba mountains and Darfur fled to the capital to escape the conflict and bloodshed. These internally displaced persons had no choice but to settle in shanty towns around the city where basic needs and services were largely non-existent. Many children took to the streets; some by choice, others by necessity.

Camiss, an ex-street child, likens life in the city’s markets to life in a jungle – “you must be like a tiger to survive”. Kids not only struggle to feed themselves there; they face lives of violence, regularly receiving beatings at the hands of the police, they are prone to resorting to theft and drug abuse, and fighting is commonplace. Though they stick together in groups for protection and companionship, they are very much on their own; they have no one to care for them, to support or encourage them.

However, one day, Camiss’ life changed dramatically. He met a teacher from the Omdoman centre for street boys and was given an alternative to life on the street. Camiss is handicapped, and the teacher took him to a hospital to receive the care he needed but could not afford. In the centre, he also received an education. When old enough, he moved on to a second centre in Al Jeref where, along with his academic subjects, he studied metalwork. Now he lives at the centre, teaching metalwork and helping to find boys on the street who, like him several years ago, are most in need of care and support.

Where would Camiss be without the centres? “I ask myself that question every day … Maybe I wouldn’t even exist”. Camiss and the other teachers at the centre, several of whom were also once on the streets themselves, know they cannot help all those in need. “There are too many to take all of them; you can take some, though, and these boys will grow up and become good men, men who can do good things in this country.”

More details of our endeavour and the projects we visit can be found on our website – www.tuktuktravels.com. The best way to keep up to date with our progress is by ‘liking’ our Facebook page, ‘following’ us on Twitter or checking out our live map. If you’re interested, please do get in touch – we’d love to hear from you!

Tuk Tuk Travels

- 1

- 2

- 3Currently reading

Tuk Tuk Travels: Entry 2: Streetwise in Sudan

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

No comments yet