In their fourth travelogue, Rich and Nick speak to two young genocide survivors who founded Healing through Arts and Drama, a project set up to help educate people about the importance of reconciliation and unity.

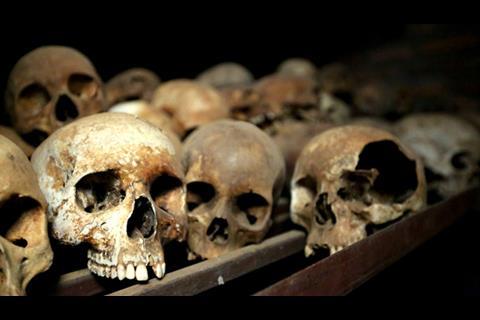

In the eyes of the outside world, Rwanda cannot escape from its brutal past – the 1994 genocide that wiped out 800,000 of its population, created two million refugees and displaced a further 1.7 million within the country. The sheer brutality and clinical nature of the massacres was hard to comprehend. We visited the church in Nyamata where 10,000 Tutsis fled seeking refuge and instead faced slaughter at the hands of their Hutu neighbours – fuelled by the manipulative propaganda that tore the country apart. The ethnic extremism somehow empowering perpetrators to carry out such savage and mindless violence was infectious; not only were these acts carried out by young men serving in the army or militias, blindly following orders from above; children killed children, mothers carrying babies killed mothers carrying babies. The schools even played a role, separating Tutsis and Hutus and registering their ethnicity – facilitating their segregation and the subsequent tragedy.

Charles and Steven, two young Rwandans, founded Healing through Arts and Drama in 2010. Charles was one of the 16 people and the only member of his family who had miraculously escaped the Nyamata slaughter. Steven, another genocide survivor, was quick to point out that Rwanda doesn’t begin and end with genocide; the tragedy that befell the country cannot be escaped however – “it was a betrayal; even the heavens had denied the Tutsis by then.” Dying became a way of life. People lived in despair and lost all hope. Even today, Steven explains, Rwandans are in a position where they’re not able to hope, to dream. These wounds still exist and they are still fresh.

For both survivors and criminals, the nightmares are still there: “If those nightmares and bad feelings are suppressed, they are just like magma in volcanoes. The volcano just covers it up but it heats up in there and at some point it finds its way out. If people don’t have a chance to talk about the emotions they are harbouring and suppressing, at some point it will explode.” You can’t know what people are harbouring, we’re told. “Imagine a bottle of dirty water; the sediment sinks to the bottom and sometimes you can’t see it. Shake it though and that dirt rises and comes to the surface.” When you see Rwandans today, everything seems OK; they seem like clean water. You don’t know what sentiments they’re hiding though. “If something shakes them, then you can see there are people who are still suffering … Maybe in ten years, in twenty years this may happen; it can happen again.” Even children born after the genocide can inherit this trauma and are at risk.

“Tutsis and Hutus are just names. You can’t find reason behind this insanity. What’s important is to unite people; if people are united, there is nothing that can stop them … Survivors and criminals need to try to forgive each other and themselves, to accept who they are and to heal.” That’s where the arts come in … “When you listen to music, it gives you a rhythm, it gives you a kind of introspection; you think about and consider yourself. It can heal. In Rwanda, there’s a need to educate people about the importance of reconciliation and unity; we are trying to use music, poems and drama to do this.”

“When people mention education, they think of it as a matter of academics, of being in school or a laboratory; but education is not just giving people knowledge. What we’re doing is education too; we’re trying to show people how to use their minds, their feelings, their talents and their potentials to cultivate positive thinking. The people who organized this genocide and the people who carried it out, they were highly educated but they lacked something – a sense of humanity and recognition of human value. Man is a product of evolution; people change – they can be made bad or good. Though Rwandans lost hope, they can learn how to hope again. It’s a process. You have to remember the past, learn from it and move forward.”

“We need hope,” Charles explains, “that’s where we can find a bright future. We’re working with the hearts of people who’ve got these wounds; they don’t believe they can forgive; they don’t believe they can confess what they’ve done. When they sing though, when people hear these songs, it can heal them. You can connect with people’s hearts, with their emotions. That’s where they can achieve reconciliation, just as we did.”

More details of our endeavour and the projects we visit can be found on our website – www.tuktuktravels.com. The best way to keep up to date with our progress is by ‘liking’ our Facebook page, ‘following’ us on Twitter or checking out our live map. If you’re interested, please do get in touch – we’d love to hear from you!

Tuk Tuk Travels

Two teachers, Nick and Rich, travelled around the world in a tuk tuk to visit charitable projects and promote English language teaching. We followed their adventures here on onestopenglish.

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- Currently reading

Tuk Tuk Travels: Entry 4: Rwanda

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

No comments yet